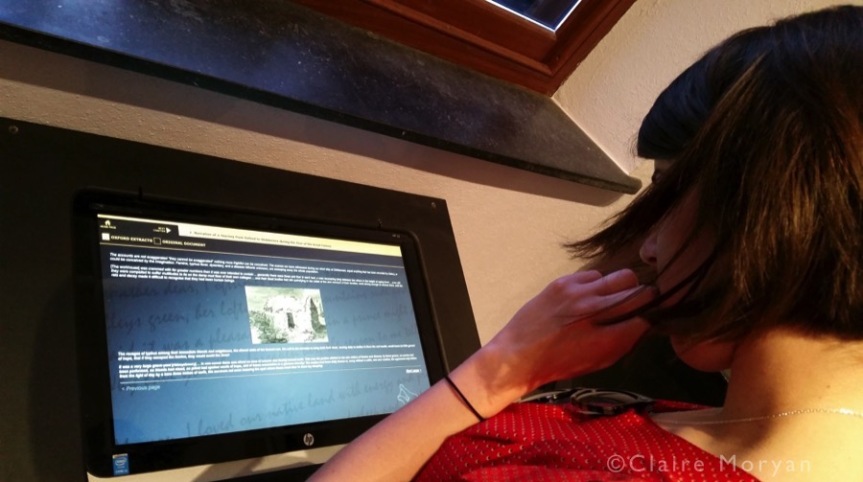

In 1759, Arthur Guinness took out a 9,000-year lease on a 4-acre brewery at St James’s Gate, which he turned into the Guinness brewery. The original signed loan is displayed at the beginning of the self-guided tour at the Guinness Storehouse, a building which spans 7 floors and is part theme park, part brewery, and part museum.

I need to address one, possibly major, caveat right at the beginning. The storehouse is not a brewery tour. The self-guided tour does discuss some aspects to the creation of Guinness, which I will discuss below, but it is not as authentic as a typical brewery or distillery tour. Apparently, there is a small installation of the brewing process, but it was closed at the time of my visit. Visitors who desire a classic brewery tour should go elsewhere.

The storehouse begins with the essential ingredients of Guinness-making and beer-making in general, namely barley, hops, yeast, and water. The storehouse explains why each ingredient is used and how much Guinness uses of each. Making Guinness seems to lie in tradition, as the brewery buys each ingredient from the same regions (for example, the water used in the brewing process is piped from the Wicklow Mountains, not from the nearby murky River Liffey). Such traditional values even produce legends. The legend is that, since Guinness yeast is always and only grown on site at St James’s Gate, it comes from the original strain Arthur Guinness used during his time as brewmaster. Whether or not it is the yeast from 1759, the brewery has transferred some yeast from one brew to the next to ensure consistency since the 19th century. Since consistency is key, some yeast is also continuously locked away in case catastrophe would mark the end of Guinness.

The next floors discuss transportation, advertisement, and tasting. Some sections, such as transport, are dealt with in passing, more to add flavor to the overall experience as opposed to the more academic treatment you would expect at a museum. What Guinness does as a museum, however, they do well and innovatively. The cooperage section, for example, not only displays the different tools needed to make barrels, but also describes the now obsolete process—it took years to become a master cooper—through a 1954 video of a Master Cooper making a new barrel. The advertising section, complete with a “zoo” of Guinness animal mascots, is complemented with a theatre, which plays Guinness commercials, and an iPad station where individuals can scroll through commercials, posters, and newspaper advertisements.

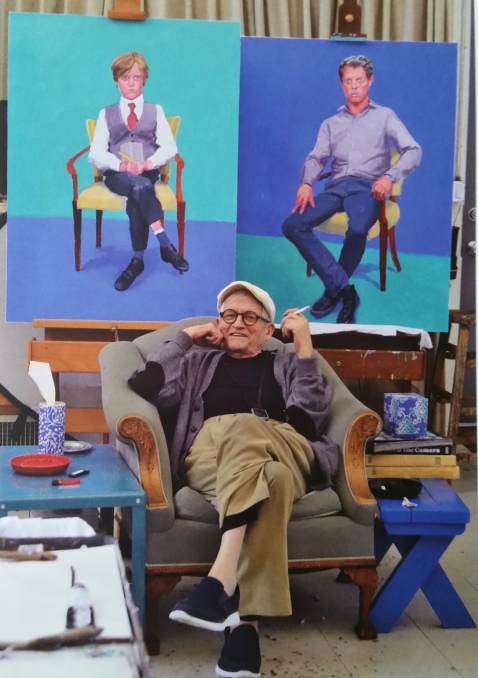

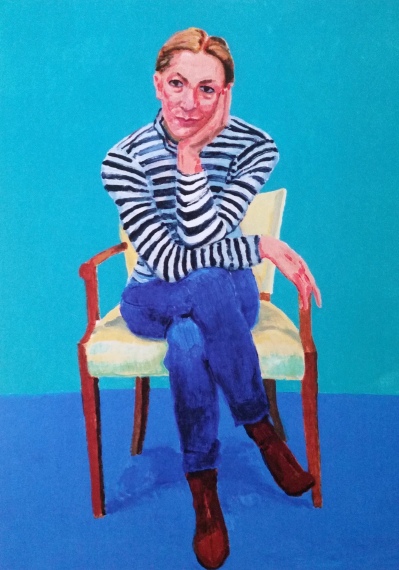

Another major highlight of the tour is the tasting experience on the second floor. Upon entering, the room feels like the Wonkavision room from Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The stark white room (lest the other senses be distracted) houses four atomizers that disperse the scents of Guinness’s ingredients for the visitors to smell. From there, the visitors grab a small taster of Guinness and are ushered into a dark room surrounded by portraits of the great men of the Guinness family (including Arthur himself) in order to drink the taster. While the atomizer half of the taster session is unlike anything else I have personally experienced, the dark tasting room seemed superfluous. Does one truly need portraits of the Guinness men in order to have a proper tasting?

The ticket into the storehouse comes with a complimentary pint or soft drink that can be exchanged once, but the visitor has several different options for how to exchange the ticket. One way is at the Gravity Bar on the seventh floor, a 360-degree glass-walled bar which provides breath-taking views the city’s sites. Another way is at the Guinness Academy on the fourth floor, where visitors learn to pour the “perfect pint” of Guinness (anyone who has seen a bartender pour a pint of Guinness knows there is a process).

The third option is Gilroy’s on the second floor, where the ticket can be exchanged for a flight of three 1/3 pints from a choice of 8-9 varieties of Guinness. Regardless of the chosen exchange, definitely step into this last bar. Extra free tasters of new beers are passed around at the top of the hour (the Guinness Dublin Amber Pale Ale is phenomenal) and then as a surprise, Irish music and dancing ensues.

Overall, the Guinness Storehouse is a great experience, but rather than a museum about beer, it is more like an amusement park for beer. While that is not a bad thing—it is fun, especially if you love the famous stout—the amusement park-like crowds become overwhelming in some of the confined spaces. Thus ensues some pushing and overcrowding.

The Guinness Storehouse is open seven days a week from 9:30 AM – 5 PM. Adult tickets depend on time of entry and “experience” add-ons, but start from €14 and include a complimentary pint or soft drink.

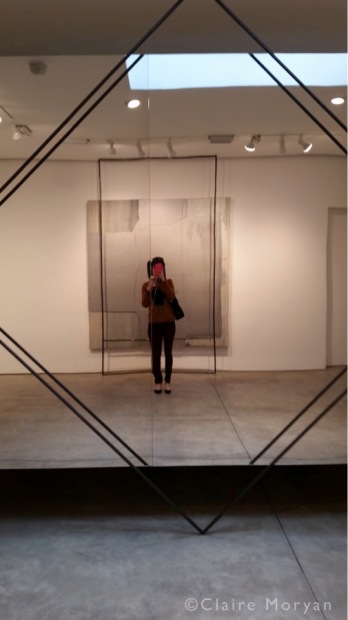

It would be incorrect to say that these two exhibitions went together; simultaneously, it is incorrect to say that they do not. The use of mirrors and steel rod-structures links the two installations together, but the essence and mood of each work could easily come from two separate artists. The fact that the same artist can create different, yet united, installations demonstrates how creative the mind can truly be. Through careful placement he is able to connect seemingly disparate items into a unique and united experience both individually and across two gallery spaces.

It would be incorrect to say that these two exhibitions went together; simultaneously, it is incorrect to say that they do not. The use of mirrors and steel rod-structures links the two installations together, but the essence and mood of each work could easily come from two separate artists. The fact that the same artist can create different, yet united, installations demonstrates how creative the mind can truly be. Through careful placement he is able to connect seemingly disparate items into a unique and united experience both individually and across two gallery spaces.

Walking around the grounds, the heritage service’s dedication is clear. Even though there are not enough funds to fully restore Charles Fort, there are small things that catapult the experience at the fort to a higher level. An explainer stands at the ticket booth to give a brief explanation of the fortress layout. A beautiful mosaic map has been inlaid in the ground at the entrance. And, perhaps most importantly, you can enter the fort up to a point before paying. This means that you can still see what the fort has to offer, before paying the reasonable price of 4 Euro for an adult ticket.

Walking around the grounds, the heritage service’s dedication is clear. Even though there are not enough funds to fully restore Charles Fort, there are small things that catapult the experience at the fort to a higher level. An explainer stands at the ticket booth to give a brief explanation of the fortress layout. A beautiful mosaic map has been inlaid in the ground at the entrance. And, perhaps most importantly, you can enter the fort up to a point before paying. This means that you can still see what the fort has to offer, before paying the reasonable price of 4 Euro for an adult ticket.