Perhaps it is because I am American, but when I think about space, it is Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and John Glenn. Soviet Russia does not feature much except perhaps, for Sputnik (first satellite) and Laika (first dog). This past Christmas I was fortunate enough to get free tickets to see Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age at the Science Museum in London. I had heard good things about this exhibition, and I was ready to expand my knowledge.

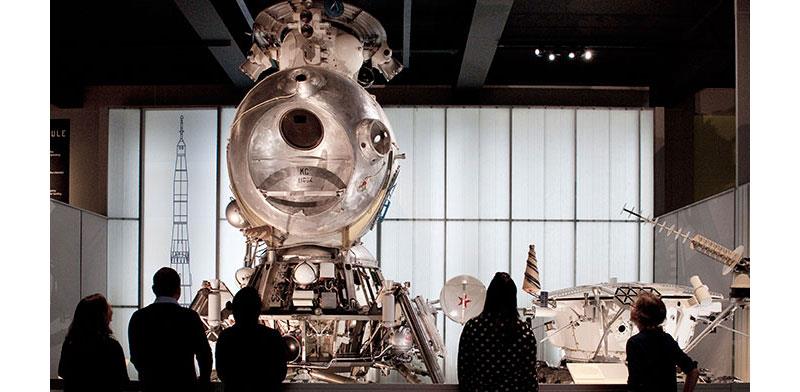

The exhibition is everything you would expect and a whole lot more! The Science Museum has two original spacecrafts: the one piloted by Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space (Vostok 6, above top), and the first 3-manned capsule (Voskhod 1). Seeing the capsules up close, with all their wear and tear, is fascinating. The exhibition also has many official engineering models of probes and landers, along with equipment that flew into space. The last major room features a wall of space clothing (e.g. compression suits and space suits) throughout the ages and technology, like space showers, sleeping bags, and toilets.

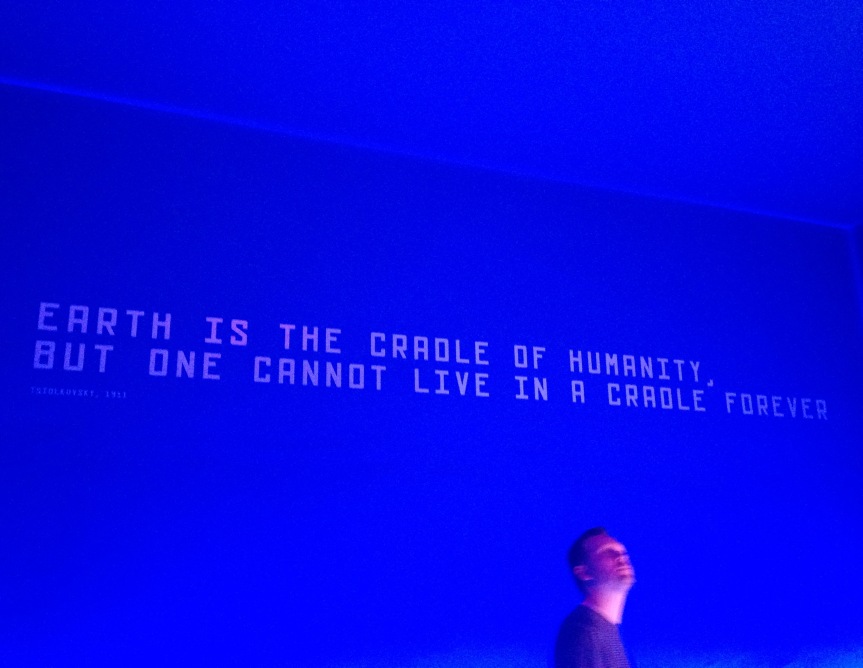

Giant pieces of machinery are exciting to see, but they can be hard to make accessible to the non-science public. Cosmonauts, however, surpasses a normal science exhibition in a number of ways by exploring non-scientific concepts. Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are welcomed by a 1921 painting by Konstantin Yuon, New Planet (above), about the October Revolution of 1917. The first area, covering the pre-history of Soviet spaceflight, blurs the lines between science and science fiction. Philosophers, authors, and scientists dream about new worlds and life in space with conceptual sketches of space walks, space stations, and air locks more than twenty years before the launch of Sputnik I.

Other objects highlight the reactions from the awe-inspiring achievements of the Soviet space program. Near the display models of Sputnik, Luna 3, and other satellites and landers, a champagne bottle is displayed, given to the Soviet Academy of Sciences by vintner Henri Maire, who offered 1,000 bottles to anyone who captured the dark side of the moon. There are pieces that speak to the cosmo-mania that exploded following the program’s initial successes. On the walls are letters from farmers and school children begging to become cosmonauts. Teacups and nesting dolls had the cosmonauts’ faces on them. Cosmo-mania then spread worldwide: images show Yuri Gagarin, the first person in space (1961), as an international celebrity who toured the world, receiving a signed photo from the Royal Family (humorously, it was a trade union—not the Queen—who invited Gagarin to England).

The exhibition also covers the affect the Cold War had on space engineering, turning it into a competition. Posters celebrating successes in space, like the one to the left, deliberately redesigned the rocket, lest other countries realize how the Soviets made them. Sergei Korolev, the director of the Soviet space program, was not publicly named until after his sudden death in 1966 because the government feared America would assassinate him. Korolev had previously been placed in the Gulag during Stalin’s Purges of the 1930s.

The second main room is filled with model displays, dedicated to the rapid progression of “firsts” for the Soviets. One object in particular summarized the feelings of Soviet citizens to these achievements: a student’s lab coat, emblazoned with “Space is ours!” to celebrate Gagarin’s first spaceflight. This area reaches a climax and shows that all that is left for the USSR is to put a man on the moon.

America’s achievements, therefore, are only highlighted once—the Lunar Landing of 1969. The exhibition shows the landing footage on a 1960s television in an empty, curtained-off room between sections. The separation from everything else in the exhibition evokes a certain amount of sympathy. In a way, it reimagines how the Soviet Union space program likely would have felt: shocked, alone, and disappointed. Kennedy’s announcement leads to the next room, where the visitors learn that the Soviet Union then hid from the public that they had nearly completed a moon-landing project, Lunnily Korabl, a model of which is on display.

I feel, though, that much of the Science Museum’s use of multimedia detracts from the exhibition. In the first and second sections, historical video clips play on spare walls without any context or explanation. Assumptions can be made about some videos—for example, a video of dogs is likely the training of the space dogs—but other clips could be anything. Additionally, a recording of clapping plays intermittently, for no reason I could see. Classical music also plays in this area, and Russian pop music plays in the last room, both without any explanation.

A political and historical abstention pervades the space, leaving the Soviet Union undefined and contextless. While the word “Soviet” is written on many panels and labels, one can walk through the exhibition without registering the term at all, mistaking Soviet Russia for modern Russia. The striking display of Korolev’s possessions from the Gulag is also bereft of context. The labels relay why Korolev had been interned, but fail to define the Great Purge or its atrocities, or state that the Great Purge severely stunted Soviet Russia militarily, politically, and scientifically—for this exhibition’s purposes, specifically in rocket technology. Korolev’s internment confusingly comes off almost as a rags-to-riches sort of story: a man, once imprisoned, has risen to become the secret director of the soviet space program. There are many reasons for these absences and omissions, the most likely being the Russian government’s involvement in the exhibition. As the majority of the items have been loaned from Russia, there may have been editing authority over the labels, either explicitly or implicitly. I do believe, though, that there could have been a middle ground for simple explanations of basic historical facts.

I laud the curators’ decision to fuse science, social, and artistic perspectives together, because it gives the Space Race, and the Eastern side of it, greater depth. Although some ideas could have been developed in more detail, the best thing about Cosmonauts is the inclusion of artistic expression and societal reactions.

But spaceships are really neat too.

Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age is on at the Science Museum until March 13, 2016.